Trump has promised environmental deregulation if reelected. Would it stand up in court?

The former president lost in court. A lot.

Should Donald Trump win White House on Tuesday, one of the most consequential impacts could well be his plans to dismantle environmental rules that have been a thorn in the sides of developers and industry lobbyists for decades.

If he comes out on top in the race, Trump would restart work that he began during his first term when he rolled back more than 100 environmental rules — touching on protections for everything from endangered species to public lands to the air and water.

But legal experts say the sheer scope and pace of that deregulatory work in his first term obscures a potentially important part of the fight.

When those deregulatory actions were finished, they were invariably challenged by interest groups and Democratic attorneys general. And when they were challenged, it turns out that the legal underpinnings of the Trump administration’s deregulatory agenda often fell apart.

In other words, Trump’s first administration lost in court. A lot.

“They did not do well in court largely because of what they did poorly during the regulatory process,” Don Goodson, the deputy director of the Institute for Policy Integrity at New York University School of Law, told Landmark.”They had a lot of procedural problems when issuing their rules, and they also had poor analyses supporting their rules.”

He continued: “Basically, they were just not doing a great job issuing rules, which contributed to a historically low win rate for the administration in court.”

A drop in success

While the former president memorably claimed that the American people would become “tired of winning” should they elect him in 2016, his administration’s record in defending the slew of major rules he issued during that time falls short of the mark.

According to data compiled by NYU’s institute, Trump’s administration successfully defended just 31.2% of the 77 major rules that were issued — compared to a 51.7% win rate during the Obama administration, 54.8% during the second Bush administration and 63% during the Clinton administration.

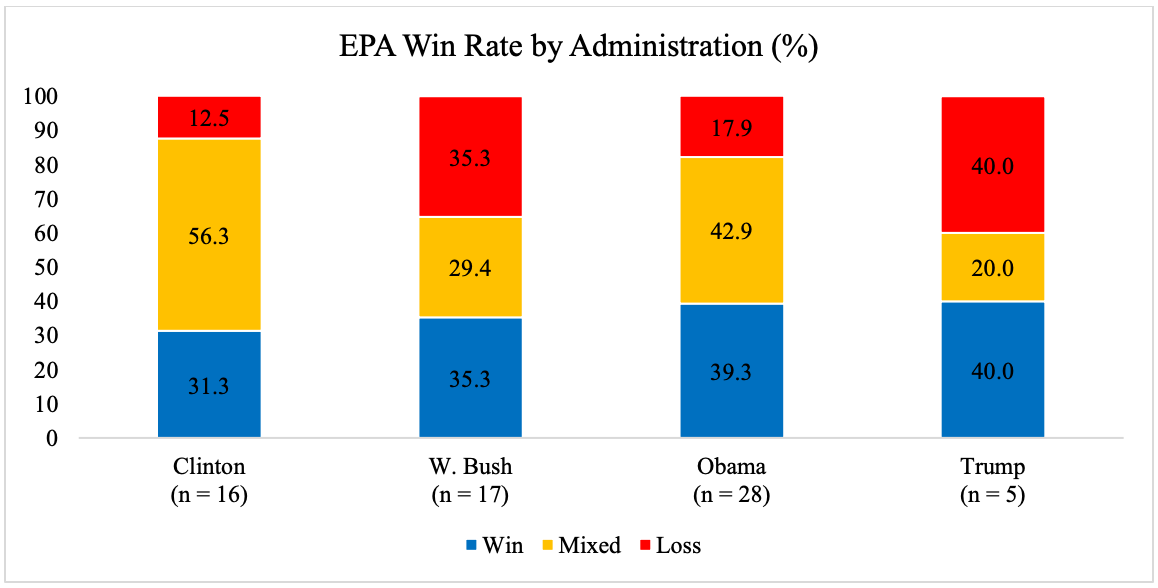

While the win rate varied depending on agency, of special note is the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which is challenged in court more than any other individual agency aside from the Department of Health and Human Services (which became the focus of numerous fights during the rollout of the Affordable Care Act).

During Trump’s first term, the EPA lost in its defense of major rules roughly 40% of the time, compared to just 17.9% loss for the Obama administration. The rate was slightly worse than the 35.3% loss rate during the Bush administration and noticeably worse than the 12.5% loss rate during the Clinton administration.

“It did not really improve over time,” Bethany Davis Noll, the executive director of NYU Law’s State Energy & Environmental Impact Center, told Landmark.

She continued: “While there were certainly a lot of procedural violations (like notice-and-comment violations) at the beginning, those continued later, too. The problem for the administration was that the governing statutes didn’t allow them to do what they wanted to do, and so that was the main reason they kept losing in court — not just a failure to comply with procedural rules.”

Learning from the past

Whether that trend continues during a potential second Trump administration is up for debate, and each of the other presidential administrations mentioned above had higher agency win rates for major rules issued in their second term.

But experts who spoke to Landmark are skeptical that those earlier losses would spur introspection and a significant legal strategy shift.

Seth Jaffe, an environmental compliance and regulatory attorney at the law firm Foley Hoag, told Landmark that one thing that could tip the scales in Trump’s favor is the makeup of the courts themselves.

Trump appointed a whopping 234 federal judges during his time in office, meaning there are that many more potentially sympathetic judges on benches across the U.S. now. President Joe Biden had named 213 judges as of late October — and roughly half of all the federal judges in the country were nominated by one of the two men.

Trump was “stacking the deck,” Jaffe said. “And in fairness, everybody tries to stack the deck at a certain level. The notion that judicial nominees are all supposed to be neutral and objective — it’s never been true, and there’s no reason why it should be true.”

He continued: “But none of them were ever affected to the extent Trump nominees have been affected by their political position. That’s all that matters to them, quite frankly, as far as I can tell.”

And the makeup of the federal bench has become ever more important thanks to the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent landmark ruling in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo.

That decision did away with the so-called Chevron doctrine, which told judges to defer to agency interpretation of laws so long as the interpretation was reasonable. Instead, judges have been charged with more directly interpreting statutes, and deciding whether agencies interpreted those laws correctly.

Davis Noll is skeptical that the fall of the Chevron doctrine is a home run for a potential second Trump administration in the courts, though.

While the demise of Chevron has generally been seen as potentially devastating for environmental protections, there are some who have argued that it may be more difficult for agencies like the EPA to roll back environmental protections under laws like the Clean Air Act or Clean Water Act, since those laws were written with protection in mind.

And removing those protections wouldn’t be consistent with the text of those laws, potentially.

“I would guess that a second Trump administration would still be looking to do things in line with his policy goals and that the statutes would still stand as a significant barrier,” Davis Noll said. “This may end up being even harder of a hurdle for his administration to get over now that Loper Bright has given more power to courts to say what the statute says.”